New Spiritual Care Minor Prepares Students for Patient Care

Kettering College challenges its students with rigorous academic courses and clinicals, but we also strive to help our students grow to be the people they want to be spiritually. Our required religion classes encourage students to first know themselves before they serve others. Self-awareness and spiritual health are goals students often meet without considering the importance of such qualities prior to enrolling.

Students can now take these valuable religion courses and earn a minor in spiritual care, being offered for the first time this semester. This minor allows them to use their 12 credits of religion they must take anyway along with three additional credits outside of those classes. Other classes include options such as a sociology class, cultural diversity in healthcare or a narrative in medicine course as a humanities elective.

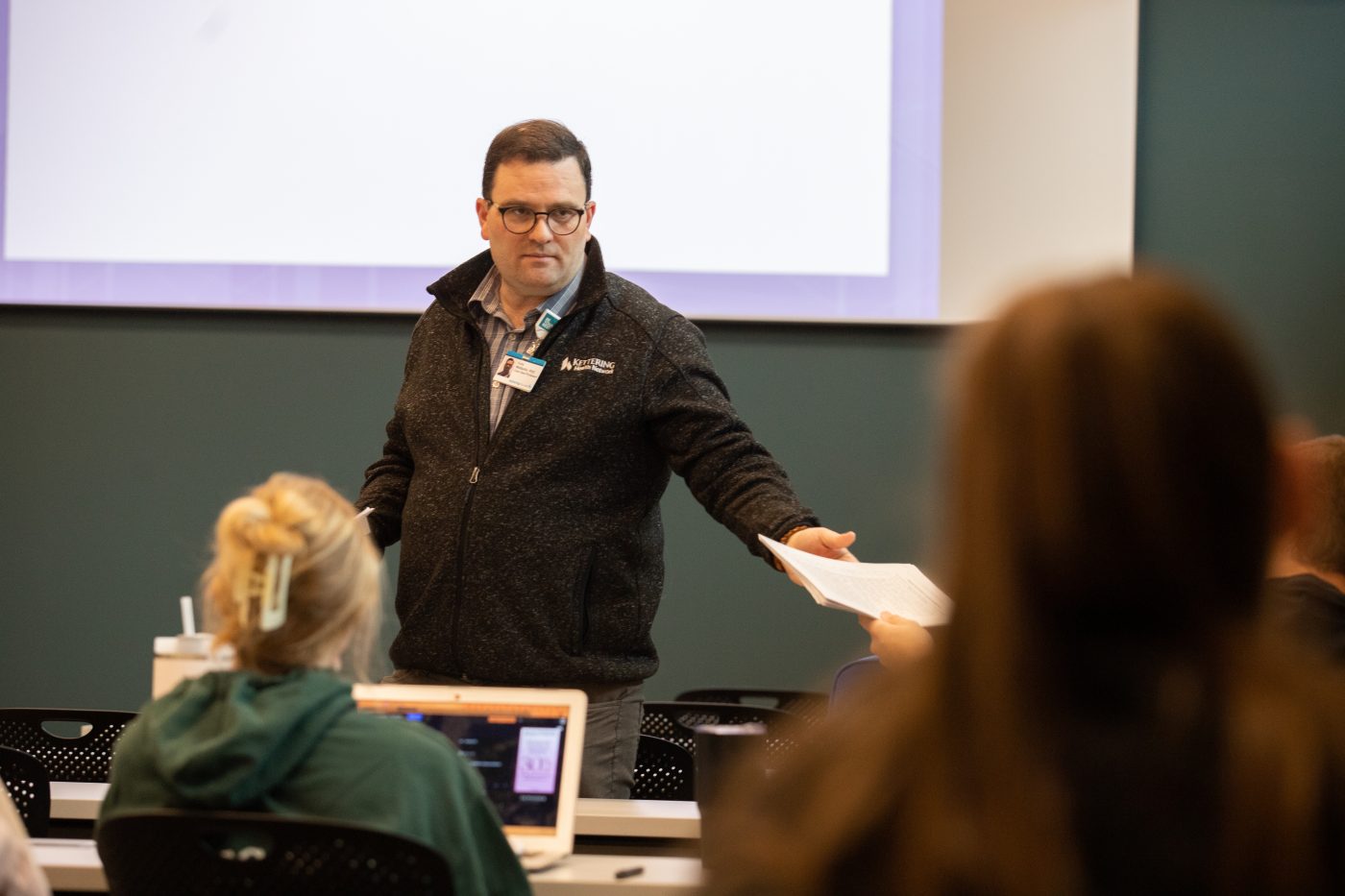

Humanities chair and professor, Dr. Cory Wetterlin, PhD, is excited about the newly added spiritual care minor as an option for students. He says adding this minor to their resumes gives students an advantage and a talking point in an interview that shows a hiring manager the student has worked on critical skills needed to serve others with empathy and care.

Spiritual care in general requires a student to discover their own spiritual narrative, which consists of things such as their culture, religion, and economic and social backgrounds. Working to identify their own personal spiritual narrative is an ongoing journey, and one that nudges them to look at themselves with curiosity and honesty. Doing this grows students’ empathy, listening skills, and ability to be more present with patients. They show up for patients in ways the patient needs according to the patient’s spiritual narrative, even when it might vastly differ from the student’s.

Professor Wetterlin says we all have a spiritual narrative, even for those who are not part of a traditional belief system. We all yearn for meaning, purpose, and connection, so we are, therefore, all spiritual. He challenges his students a step further by proposing humans are all religious in that we all have habitual practices we tend to, whether based in faith or not, that we do to achieve meaning, purpose, and connection. Profound discussions such as this are what engages students to begin considering their own spiritual narrative to create a space where spirituality is a topic that is no longer taboo or off limits.

This sensitivity of bringing spirituality up to patients is a common concern brought up in Dr. Wetterlin’s classes. To this concern, he asks students, “Well, how did it feel the first time you had to ask a patient about their sexual history?” Or he asks the sonography students, “What is something you did in your clinicals that made you uncomfortable at first?”

His point is healthcare professionals have to ask and do very personal things that are uncomfortable at first, so once they begin to find out that they can get used to asking about spirituality we begin to normalize the topic of spiritual health as an essential component to wholistic health, so we can learn how best to meet their needs and beliefs. He reminds students that 80% of patients want their healthcare provider to know about their spiritual needs, but only about 10% of providers ask.

Dr. Wetterlin says he is continually receiving positive feedback from students who have taken the religion courses. They often admit they didn’t know what to think of it and didn’t want to do it, but after the courses, they noticed a difference in how they engage with patients in more meaningful ways and hold themselves accountable to striving for more connection.

In the 100-level courses, students begin a self-charting system to observe their own behavior to get them into this objective mindset where they can step back and notice. By the 300-level course, the self-charting system begins to incorporate looking for warning signs that life is out of balance and to develop emotional balance. The goal is to cultivate self-awareness on a daily basis to engrain this into students’ spiritual health. “We are affected by our interactions with patients and we need to be able to understand why we are reacting this way,” says Wetterlin. “This will allow us to offer better care and form resilience in a field that can burn us out.”

Students at the 300-level religion courses have told Wetterlin the practice helped them to see how they needed to better prioritize their lives and shift daily habits to be more present and connected to others in their family as well as patients they were serving. The classes, and now the spiritual care minor, teach self-awareness to students and the ability to step away to objectively see themselves, so they can learn to look outward.

Professor Wetterlin says, “It’s a great program that sets us apart from other colleges. Students say they feel the material is so important they can’t imagine not getting it in their curriculum since it prepares them so strongly to know themselves, so they can serve others with more balance and vulnerability.”

He adds, “This has always been the defining mark of Kettering College. We’ve been offering these classes and doing this program for years, so at this point it’s just putting a label on it and packaging it in such a way that people can recognize that it’s not just a program—it’s what we believe and we do.”

- Restructure of Student Success Center: Holistic Approach for the Whole Student

- Doris Imhoff: A Warm, Welcoming Spirit at Kettering College

- Health Sciences Professors Collaborate and Earn Grant

- Physics Professor Uses Rockets to Launch Learning

- Women’s History Month Spotlight: Dr. Paula Reams, Dean of Nursing